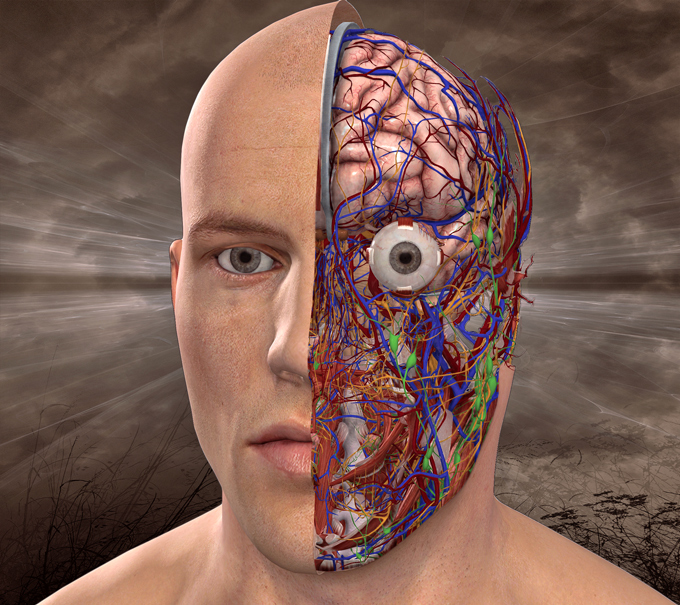

One of the most shameful episodes in the history of medicine is the use of frontal lobotomies. Despite very vague evidence of their effectiveness – lobotomies were standard procedure through the US and Europe for around two decades, until the mid-1950s. Only in US, around 40,000 people underwent a procedure that involved cutting away connections between the prefrontal cortex and the frontal lobes of the brain. The procedure was extremely dangerous – some patients died, others became brain damaged or committed suicide. A “successful” outcome meant that a patient who had previously been mentally unstable was now docile and emotionally numb, less responsive and less self-aware. On mental state examination a person with frontal lobe surgery may show speech problems, with reduced verbal fluency, he or she is lacking in insight and judgment and has problems with programming their activity.

From a modern perspective, the use of frontal lobotomies seems incredibly brutal and primitive. However, we are nowhere near as far removed from such barbarism as we want to believe. There are strong parallels between lobotomies and the modern use of psychotropic drugs. In fact, the blanket treatment of psychological conditions as if they are medical problems, and the consequent massive overprescription of psychotropic medication, has had a much more harmful effect than lobotomies.

According to some estimates, today around 1 in 6 Americans take anti-depressants.

The rate of antidepressant consumption is on the rise in so many countries. The antidepressants are now prescribed not only for severe depression, but also for mild depression, anxiety, social phobia, and more.

This might not be an issue if it was clear that these treatments worked. But it isn’t. One obvious parallel with lobotomies here is that antidepressants have become widespread without any convincing evidence of their effectiveness. Research has found that the best known “selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors” (SSRIs) do not alleviate the symptoms of depression for most patients, and are no more effective than placebos in cases of mild and moderate depression and have serious side-effects.

Many psychiatrists simply do not want to face up to the harms their treatments can produce. This is illustrated by the way the psychiatric establishment tried to avoid the implications of dyskinesia, by suggesting it was a symptom of schizophrenia. Similarly, when it became obvious that some of the second generation antipsychotics and antidepressants caused massive weight gain and metabolic disturbance, mainstream psychiatric journals published articles suggesting that diabetes was linked with schizophrenia and it was a culprit.

The suggestion that antipsychotics reduce brain volume is not new. Psychiatrist Peter Breggin made this claim over thirty years ago1, but was dismissed as a crank. Over the last 10 years, however, the evidence has become irrefutable.

The assumption that depression is associated with lower levels of serotonin in the brain is taken for granted by many people, but actually has very little foundation.

The psychiatrist David Healy described how the myth of a connection between depression and serotonin was propagated by drugs companies and their marketing representatives. In fact, as Healy states, earlier research in the 1960s had already rejected a connection between depression and serotonin. However, propelled by the marketing millions of the pharmaceutical industry, the myth of a depression as a “chemical imbalance” that could be restored by medication quickly caught on. It was appealing because of its simplistic portrayal of depression as a medical condition which could be “fixed” in the same way as a physical injury or illness.

Another parallel with frontal lobotomies is that psychotropic drugs continue to be so widely used despite massive evidence of their harmful side-effects and after-effects. Although many psychiatrists worldwide state that anti-depressants are “not habit-forming”, a 2012 survey by the Royal College of Psychiatrists in the UK showed that 63% of people who came off antidepressants reported withdrawal symptoms.

One problem here is that withdrawal symptoms are often interpreted as a “relapse” and used as a justification for continuing treatment, which continues indefinitely.

The most unfortunate aspect of this is that research has shown that most cases of depression fade away naturally within a few months, without treatment. For example, a 2012 study in the British Medical Journal found that the mean natural duration of “major depressive episodes” without treatment was just three months.

Common side effects of SSRIs are fatigue, emotional flatness and detachment, and an overall loss of personality. They are also strongly associated with sexual impotence and “movement disorders” such as akathisia – and psychiatrists often treat akathisia as an underlying problem which needs to be treated with drugs, rather than an effect of the drugs themselves.

The most fundamental parallel between lobotomisation and psychotropic drugs is that they are both based on a flawed assumption: that psychological problems are brain conditions, and that they can be “fixed” by neurological interventions.

Sorce: Psychology Today